Sparc

Illuminating houses using waste heat

Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd.

India struggles with a severe imbalance between electricity demand and supply, leading to an estimated shortfall of over 42 billion kilowatt hours. This shortfall causes frequent power cuts, especially in rural areas, where millions experience regular outages despite having electrical connections. Additionally, over 300 million Indians, mostly in rural areas, lack any electrical supply.

Urban areas receive prioritized electricity during peak hours in the morning and evening, exacerbating power cuts in rural regions. Rural residents, therefore, suffer more frequent and prolonged outages and must find alternative energy sources. With unsteady and limited incomes, they rarely afford costly systems like inverters, generators, or solar panels, relying instead on oil lamps and rechargeable torches. This energy crisis impacts quality of life, economic activities, and limits educational and health services in rural areas.

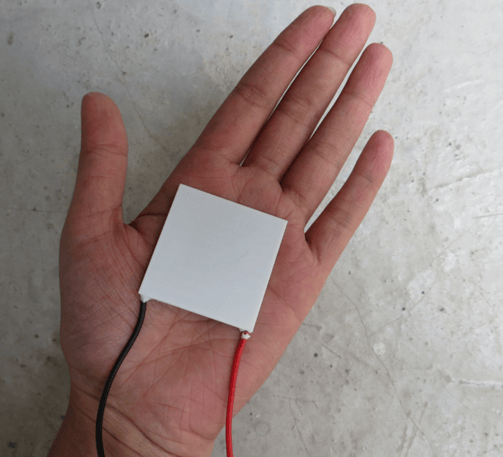

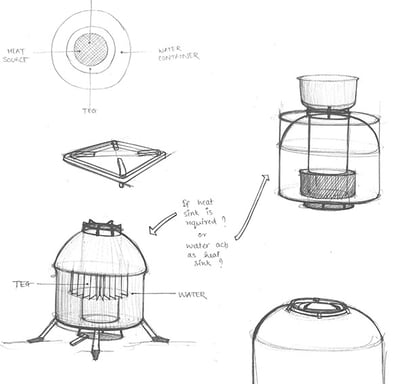

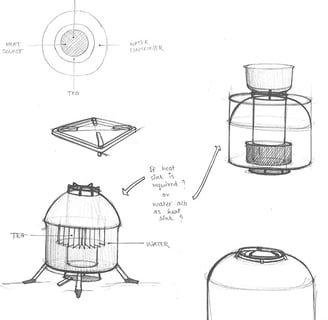

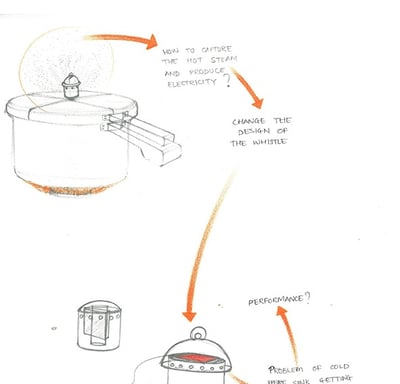

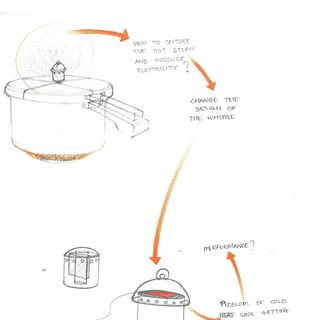

Given the frequency of power cuts and the scarcity of alternative energy sources in rural areas, this research-informed design project began with the concept of utilizing thermoelectric technology. The aim was to explore the feasibility of converting heat from existing household sources into electricity using thermoelectric chips. These solid-state devices generate electricity by creating a potential difference through a temperature differential between two surfaces. Thermoelectric devices are lightweight, compact, portable, require minimal maintenance, and are easily sourced. During initial research, the idea of utilizing thermoelectric technology was conceived and experiments were conducted to test the viability of the technology.

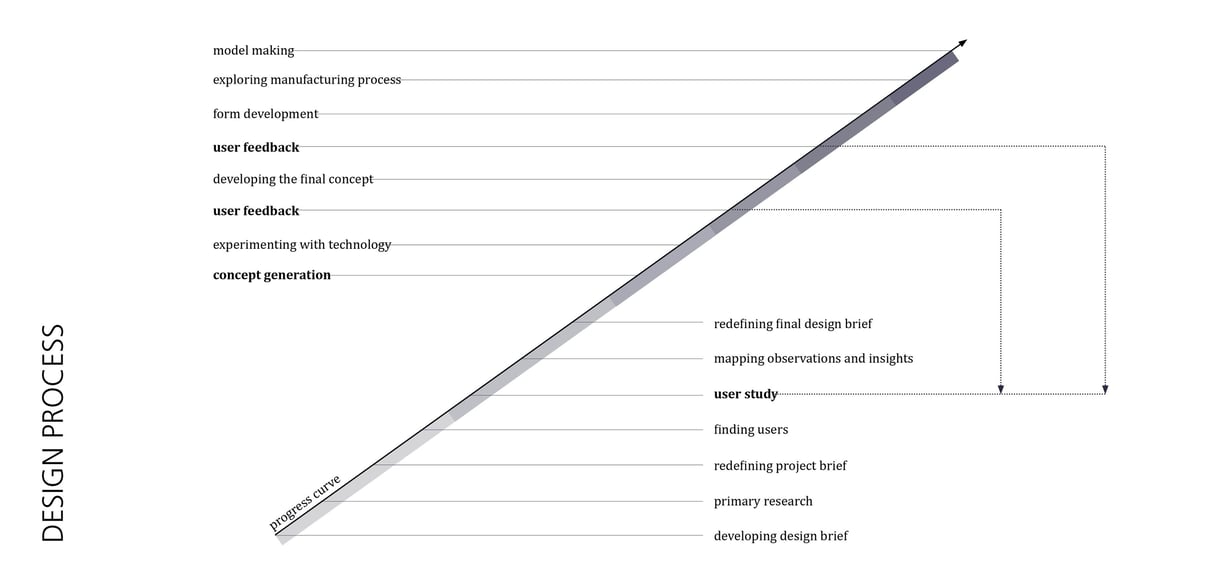

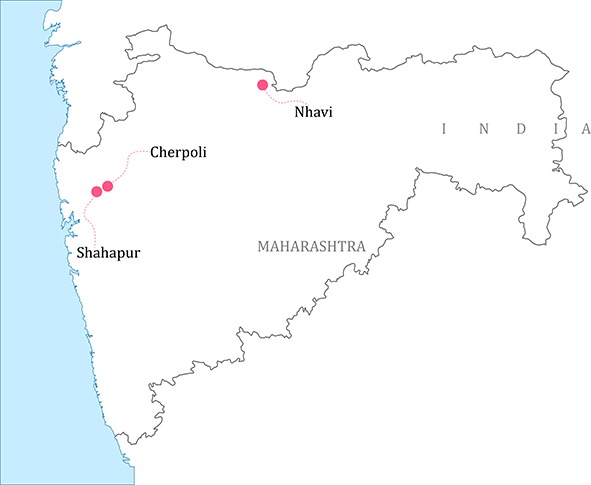

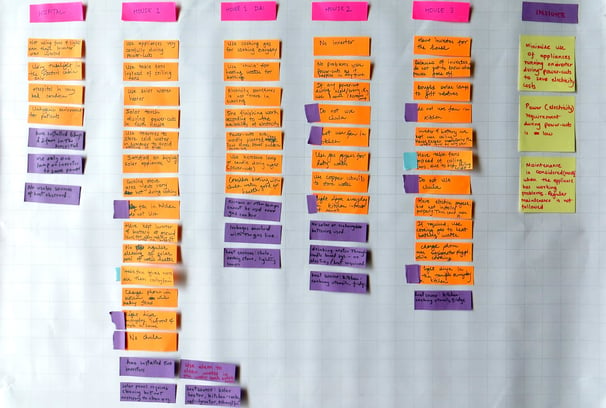

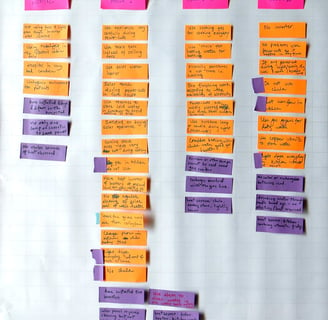

Ten households were studied at three different locations in Maharashtra. The main goal while conducting the first study visits was to understand the gravity of power-outage issues, connect with the people and keep an eye for untapped energy sources that generate high amounts of high or low temperatures in the house.

First set of user visits were conducted at Shahapur, a town in Thane district in Maharashtra. Ethnographic studies of three households in Shahapur town revealed that they were subject to power-cuts for 3-4 hours per day. Two of the houses used inverters during power-cuts while one did not.

During these visits it was observed that people had adjusted their lifestyle according to the power-cut schedules - electric water heaters were replaced by gas geysers and solar heaters, clean drinking water was purified and stored in the morning, and cooking was finished before the scheduled power-cut.

The study revealed that the energy requirement during a power-cut is low. The cooking stove, exhaust fan and the house temple were the primary heat sources at home.

Cherpoli, a semi-urban community in Shahapur taluka was visited next. Ethnographic studies of four households in Cherpoli revealed that none of them had inverters. While one house had a rechargeable torch, all of them used kerosene lamps during power-cuts which ranged in duration from 3~9 hours per day. Compared to households in Shahapur town, the socio-economic status of households in Cherpoli was lower. This was evidenced by fewer electrical appliances in the house, and the predominance of chulas (wood-fired stoves) for cooking and heating.

During power-cuts, kerosene lamps were only used during activities like eating, reading or walking around in the house. Mobiles phone flash light was also used as an alternative for a kerosene lamp. The daily usage of power was very low to cut living costs. In these houses, the chula and cooking stove were the primary heat sources.

Three houses were visited next in Nhavi, a village in Yawal taluka. Agriculture is the predominant occupation in Nhavi and hence, the income varies drastically due to changing climatic conditions and water shortages. Usually, power-cuts occur 2~3 times a day for durations totaling 6~9 hours. Similarities were noticed in the living conditions of people in Cherpoli and Nhavi, but unlike people in Cherpoli, power-cuts mainly affected the farming community in Nhavi.

In absence of a steady electric supply, people relied on diesel power generators to run water pumps in farms. However, at home, they used kerosene lamps or rechargeable torches for light. All the households had both a chula as well as a gas stove, but the chula was predominantly used for heating water and cooking, and was the primary heat source at home.

The project brief was to design a product that converts waste heat emitted from stove/chula to electricity by using thermoelectric generator (TEG) technology. The electric charge could be stored in a battery source that can power a torch or mobile phone during power-cuts.

Project brief

Findings from the three locations highlighted a common issue of frequent power cuts, though access to alternative energy sources varied by socio-economic status. Most households minimized energy use during outages to cut expenses, utilizing alternative sources only for essential needs.

Research indicated that if affordable and lifestyle-appropriate solutions for generating electricity at home were available, people would be receptive to them. Considering that cooking stoves and chulhas are standard heat sources, it was decided to develop a solution to capture waste heat from these sources to generate electricity for use during power cuts.

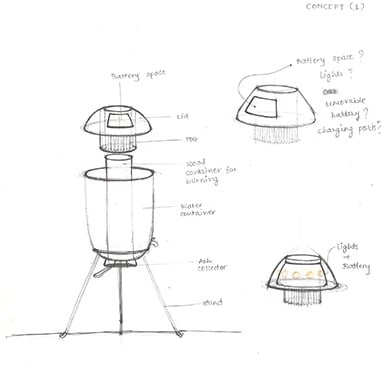

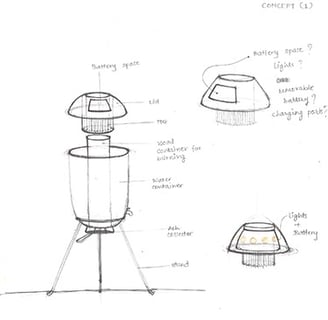

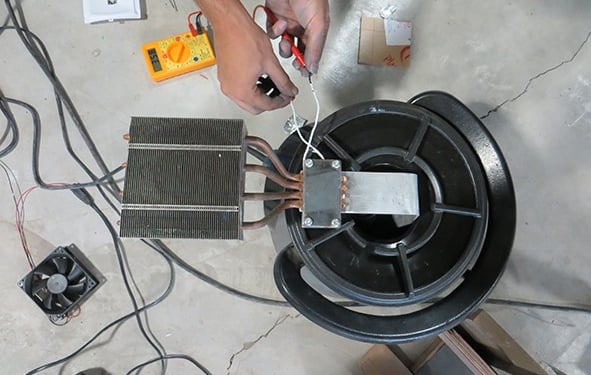

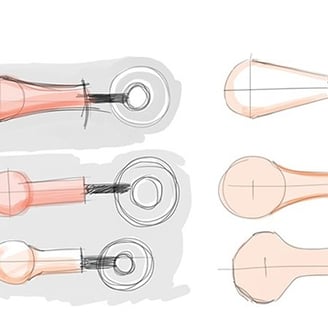

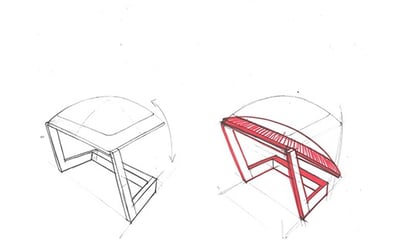

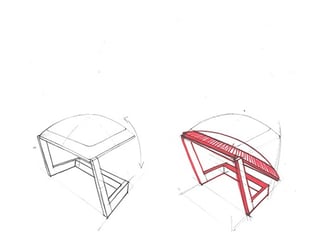

Based on the observations and insights from the visits and user interviews, a range of product concepts were sketched and working prototypes were developed. The concept generation phase started with understanding the working of the technology and testing it to figure out the limitations. Around 14 prototypes were tested to check performance on heat elimination from cold side of the chip and electricity generation. Heat sinks, water filled heat pipes, copper tubes and a variety of fans were used.

Users played a very important role in directing this research. Every modification made in the prototypes was tested by users and feedback incorporated for the next iteration. Regular visits were conducted to the houses initially studied at Cherpoli and Nhavi to gain feedback and reactions from the people. These prototypes were tested both at the laboratory in Mumbai and demonstrations were also given in public at these locations. These demonstrations helped in the evolution of the product. The mesh frame of the product that fits different stovetops was designed based on the variety of stove tops available in market.

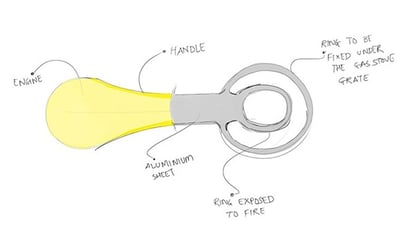

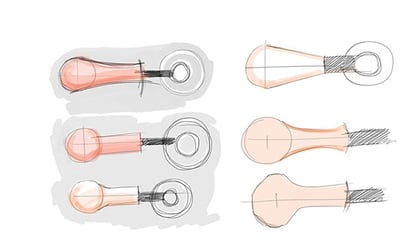

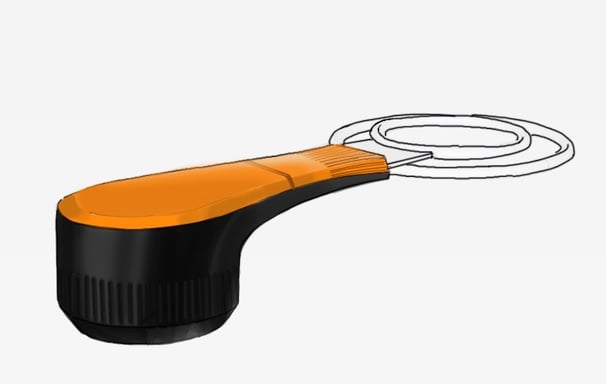

The finalized product form encases the aluminum plate, the TEG chip, the spacer block, the heat sink, the fan and the TEG circuit. The form inspiration was drawn from the shape of a flame and sketches were drawn to visualize the three-dimensional design. Foam models were carved to understand the functionality, usability and feasibility. These mock ups were also shown to the users for their feedback.

The designed form gave a compact yet dynamic look to the product while also making it comfortable to handle. The aluminum rings provided easy placement on any type of stove while effectively capturing waste heat from the stove. The rings were designed such that they would not obstruct any cooking activities while collecting waste heat from the burner.

Sparc is a product that harnesses energy from waste heat to illuminate homes. The product was designed as an affordable solution for communities at the bottom-of- the-pyramid who have limited or no access to uninterrupted electricity at home. Sparc uses a thermo-electric generator (TEG) to transform waste heat from cooking stoves or ‘chulas’ into usable electricity that can power lights and recharge mobile phones.

Sparc

This project illustrated that a design strategy rooted in user research is highly effective for new product development. The continuous cycle of research guiding design and design inspiring further research formed the core of this project's methodology.

Acknowledgement

Gourab Kar, Project guide at National Institute of Design, India.

Hrushikesh Patade, Electrical Engineer at Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Ltd.